Early spring is a busy time for maple syrup farmers, and although Maple trees may appear dormant with their leafless branches, there’s a lot going on behind the bark of their towering trunks. Let’s tap in to the science behind tree sap, the coveted ingredient behind maple syrup.

Sourcing Sap

Any species of Maple tree can be used to make syrup (Red, Black, Silver) but Sugar Maples (Acer Saccharum) are the primary source due to higher ratios of sap to sugar. On average, about 40 gallons of Sugar Maple tree sap yields 1 gallon of syrup. Different classes or “grades” of syrup are determined by the quality of the sap harvested.

“The Darker the Syrup, the Stronger the Maple Flavor”

‘Grade’ is the standard Maple Syrup ranking system used across all of North America. It consists of two things: color and flavor, and the color of a syrup determines its flavor.

“Grade A” has four color and flavor classes:

- Golden—lightest color, delicate and subtle flavor with hints of vanilla. Sourced from first sap flows of the sugaring season.

- Amber—light amber color and rich, full bodied maple taste. Typical “classic” maple syrup

- Dark—dark amber color, robust and intense flavor

- Very Dark—darkest color, strong and very intense flavor. Best for cooking and flavoring other foods.

(Note: Any syrup that fails to meet Grade A standards is classified as “Processing Grade” or “Substandard”.)

Typically, as the season progresses and temperatures rise, syrup color darkens due to decreased sugar concentration and microbial activity. However, numerous complex factors affect the color and flavor development of syrup, including frigid nights, sap handling and processing, and sap composition—the types of sugars and organic substances present in the sap.

Once temperatures consistently remain above freezing and trees begin to bud, the chemistry of the sap changes, marking the end of the maple syrup season.

What is Sap?

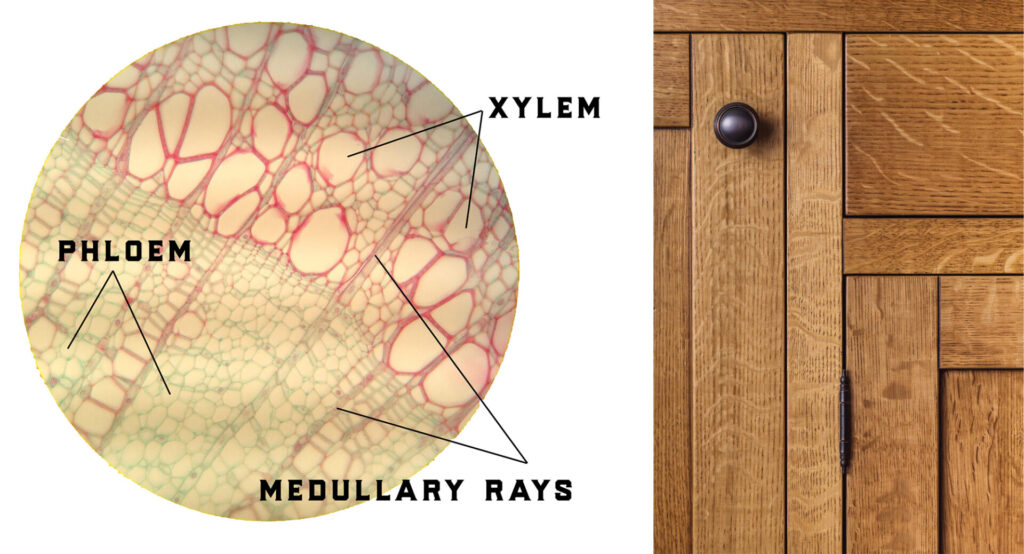

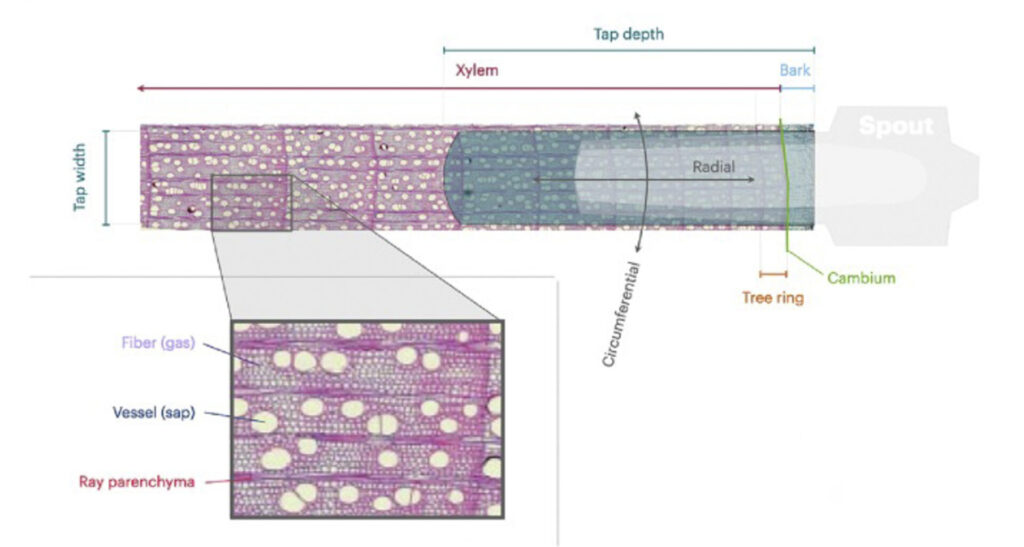

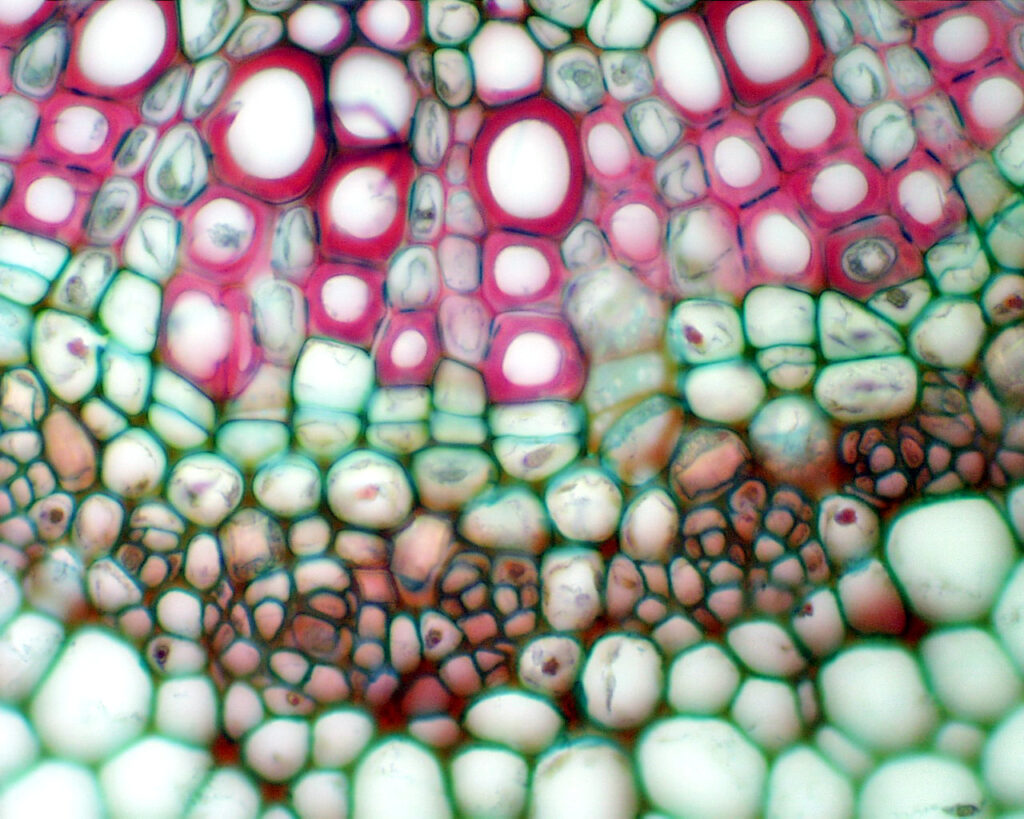

Sap is the watery fluid in plants that carries nutrients and sugars, traveling through tube-like “vascular bundles” consisting of Xylem and Phloem tissue. Let’s revisit middle school science:

Xylem tissue transports and stores water and nutrients from the roots to the leaves. Phloem tissue transports sugars, proteins, and organic molecules from the leaves to the rest of the plant.

(Note: As a tree grows, old xylem tissue becomes what we know as the heartwood of a tree. We will discuss this in a later issue.)

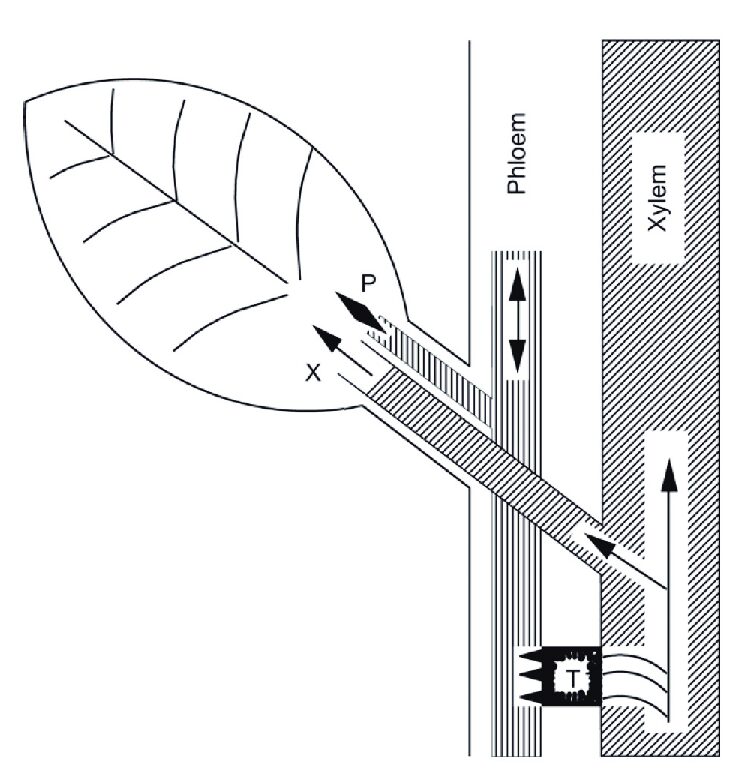

Flow of sap in a tree differs when leaves are present and absent.

In the summer, chlorophyll rich leaves convert sunlight into sugar and sap flows freely throughout a tree via phloem tissues.

In the winter, when trees are dormant, things get more interesting and this is what makes maple syrup farming pretty neat.

Medullary Rays

While xylem and phloem run vertically through a tree, medullary rays, or “wood rays,” are tissues made of parenchyma cells that run perpendicular to the growth rings of a tree. They are essential to tree functioning and survival, connecting vascular tissue from the center of the tree to the bark.

All trees have medullary rays, but they are most prominent in white and red oak when it is quartersawn.

Maple trees store carbohydrates in medullary ray cells as starch. Sugars are typically only found in the phloem tissues of plants; however, during winter, starch is converted into sugars and released into xylem ray tissue.

The sap tapped for maple syrup comes from these xylem rays, and it is these ribbon-like rays that dictate the sugar content of maple sap.

Trees with more ray cells are able to store more sugar within the tree. In the dormant winter months, this means that the sap will be sweeter.

Two things affect the quantity of ray cells within a tree: genetics and increased growth rate. The faster a tree grows, the more rays cells it will have, meaning the more sugar it can store, and the sweeter sap will be. Higher concentrations of sugar in the sap mean lighter color syrup. Every step of the process depends on the health and growth of the tree, which is why Maple syrup farmers are tree stewards through and through. Many of your local sugarbush farms are family owned, operated, and past down through the generations. Think about supporting them when you buy maple syrup, so you can be part of the stewardship cycle!

Cheers,

Viktoria

Thank you for reading! We appreciate your time and attention.